Most folks around St. John’s know about the ‘river’ under the Avalon Mall parking lot. This is Leary’s Brook. Some people may also even be vaguely aware that ‘Kelly’s brook trail’ used to follow a brook called ‘Kelly’s brook’. Interestingly, if you go looking for that brook, you will quickly find it was replaced with a complex network of underground piping. This isn’t the only ‘missing brook’ in St. John’s. As is often the case, when towns develop, small brooks get absorbed into storm water piping networks and St. John’s did this quite a bit. This is now illegal in many cases, but that just means we can talk about the ones we lost.

Before we talk about buried brooks, I want to first mention that we don’t really do this anymore*. During the suburban expansion frenzy of the 1960’s, St. John’s buried a LOT of brooks and streams, but they also did this as early as the 1800’s and you can bet that if St. John’s grew bigger, more would have been lost. See every major city in the world and how few small brooks exist. Nowadays, modern urban planning has come to the senses that brooks and waterways are worth more than just the development value of the land. They provide habitats, places for parks, and crucial safeguards against flood risks. There is also the risks of jail time for burying a brook that hasn’t been given explicit permission from the proper government authority.

I don’t want this to turn into a hydrology course so we will keep this short: the question is what is better; a natural watercourse, or a buried pipe? When the goal is to maximize development area with no regard for anything else, and the brooks are small, you pay for large pipes and bury that brook in. If the goal is just about anything else, you keep that natural water course. Hard for a duck to lay eggs in a pipe. Swapping a brook to a pipe depends on the volume of water. In days before proper urban engineering, that would be a pretty rudimentary calculation that didn’t account for larger storms. It wasn’t until after WW2 that analyzing the peak runoff became more common place and factored in high intensity storm ‘projections’. It is often why during intense rain storms, older pipes overflow and wash out roads. The higher the flow, the larger the pipe and the more expensive that gets. Engineers get paid good money to determine how much money piping will cost but we won’t get into that.

St. Johns has a lot of parks and walkways with rivers. We have the popular rivers like Virginia River, Rennie’s River, Waterford River, and Topsail River but there are more. With these larger urban rivers, one can more or less walk a decent amount of their total length, but at some point, you will reach a fork where the combined minor streams are so low flow, that you would need a chainsaw to clear a path through the woods to follow them, or you stare at a storm-water structure. The latter is the answer to ‘Where’d the brooks go? that this post is about.

Kelly’s Brook

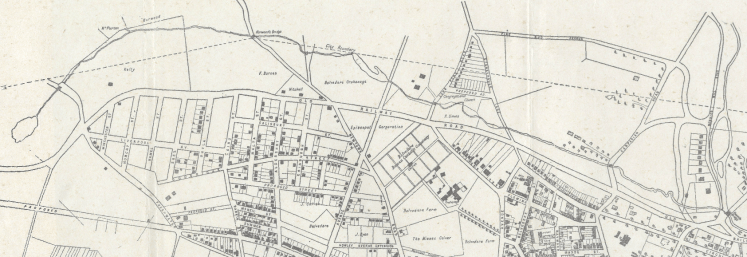

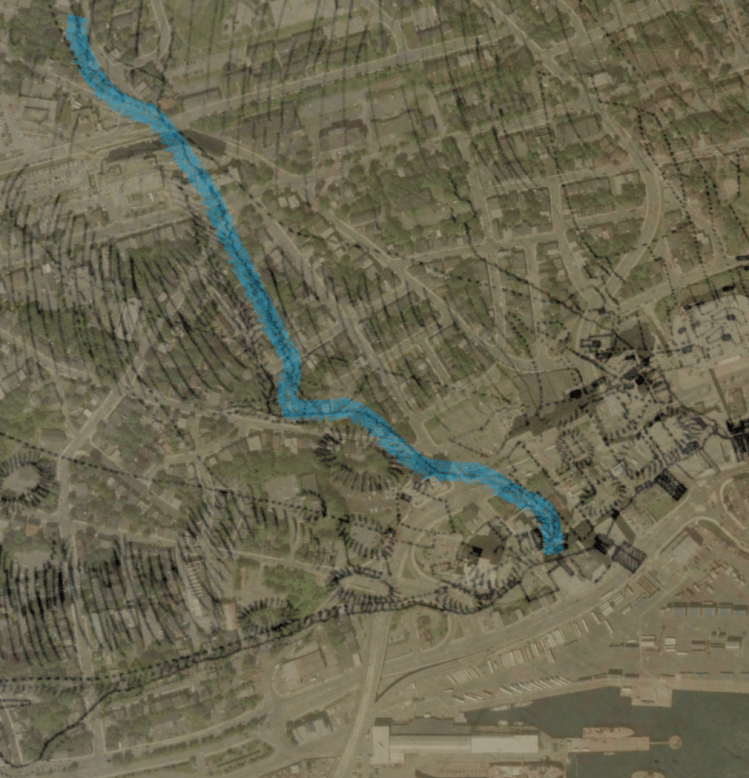

Let’s start off with Kelly’s Brook as it is one the the most prolific. Down by the Feildian fields at the bridge across Rennies Mill Road, you’ll see some culverts that stick out of a wall. Over at St. Pat’s ball field, a small section of Kelly’s Brook remains but as soon as it reaches Carpasian Road, it becomes storm water piping. So where did Kelly’s brook go? According to a 1932 survey map of St. John’s, Kelly’s brook continued along the current green space, which makes sense. Somewhere around Graves Street, Kelly’s brook split off toward the St. John’s farmers market and a small brook maybe called Horwood Brook terminated at a pond where the taxation centre rests. The old 1932 map ends, but looking at Lidar Data, the valley low points continues until around PowerPlex building on Crosbie Road.

Miscellaneous Brooks and Streams

Going back even further, there are at least 4 noted brooks in the 1765 plan of St. John’s Harbour. One starts around the new Fortis building, heads along Pleasant Street and splits in two running up parallel to Cornation Street. Another brook starts around the Convention Centre, and terminates somewhere near Cabot Street. Another Brook is essentially Carter’s Hill. The largest brook of note in the 1795 map starts around Temperance Street and follows the low laying area and had a small pond in the parking lot north of the Fort William building. The 1795 map also contains the actual Fort William. That map also has Kelly’s Brook noted, but it was deeply the ‘wilderness’ part of the map.

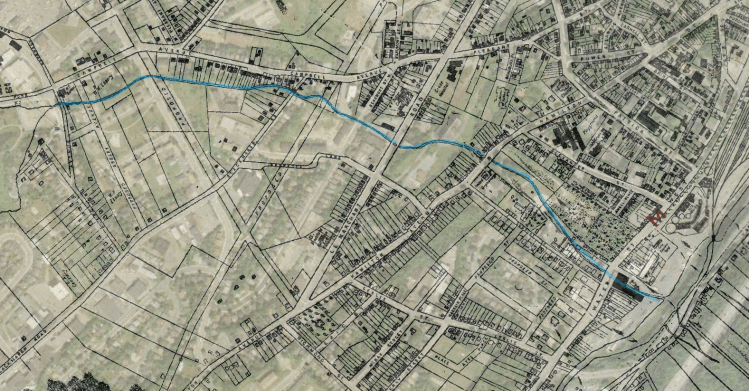

Those hand drawn maps can be corroborated by looking at the general topography of the land. However we also have post WW2 aerial imagery. We have several aerial images orthorectified (geometric distortions corrected), one of which we wrote a short blog about here.

Let’s do some rapid fire brooks. We have one starting Chuckley Pear Place, heading along Colville Place, generally along Eastaff Street, then more or less along Captain Whalen Drive to the forested area by the Nalcor building. It was called Beaconsfield Brook. In Mount Pearl there used to be a stream from Masonic Park down by Champlain Crescent. There used to be a stream from Leary’s brook around Kelsey Drive more or less above Wal-Mart to Maurice Crescent. There was another small stream from Desola Street toward 140 Ladysmith into Yellow Marsh Stream. Cutting way across the City there are 3 ponds that were just buried; on under Chancellor Park, one at Regina Place and another building 7 for Homeport Apartments.

Mundy Pond Brook

Heading west from Mundy Pond a brook is under the road until around Civic 186 where it comes out of this headwall and stays intact. There is a section under some houses on Jensen Camp road and then around Empire ave west of Jensen Camp Road, there is a small section of a brook under the street. That brook gets part points for being partially buried.

Looking west from Mundy Pond we can still see the brook but not east. The outlet of Mundy Pond Road is completely buried. Mundy Pond used to go right to the edge of Pearce Street before it was partially drained. There even used to be a little island which you can see just north of the new Mews Centre. On the 1932 property map we can see the old brook running behind the rear lots of Campell Avenue then heading under the old Grace Hospital Site.

It then went more or less directly toward the Waterford River via the Sudbury Street baseball field and park. That whole brook has been completely converted to storm piping. There are still some nice trees along the old brook path. The St. John’s Lidar still shows some minor low points but they all eventually just go over sidewalks and into the storm sewer.

Kenny’s Pond and Kent’s Pond

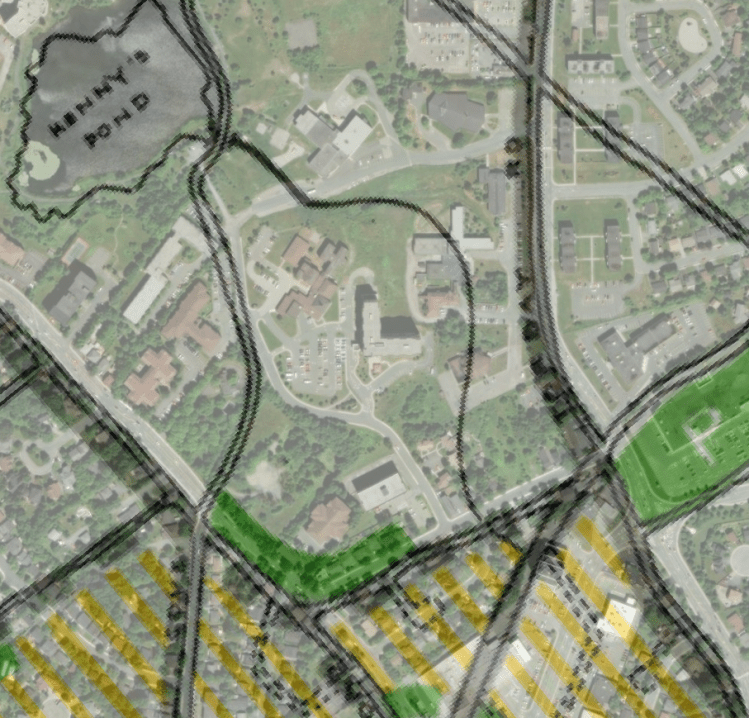

Around College of the North Atlantic Prince Phillip Drive there are two ponds. Despite their proximity, they do not drain to the same brook. Kent’s heads to Rennies River near Long Pond and Kenny’s Pond heads to Rennies but entered not far from Quidi Vidi Lake.

Kent’s pond brook drains behind the Confederation Building into a wetland. This wetland has and intake structure that for a short distance buries the brook under Allandale, to only pop back out again just opposite of Nagle’s Place. On the 1946 zoning map, we can see the the brook used to cross what is now a road two times. That is likely the culprit to why it was partially buried.

Kenny’s pond brook is a bit less clear of the exact routing. The 1946 zoning map shows a brook heading toward Horwood street but it is already buried by then. We can see a possible vestige behind 12-18 Tiffany Lane, but the short lived section enters back underground. The older hand drawn maps and the newer aerial imagery have no record of the brook after this point.

We can use lidar mapping to determine that the only plausible route was to head along Dunfield street, crossing New Cove Road, then connecting to the green space between Bristol Street and Glenridge Crescent. This brook would have likely gone through the property of 51 New Cove Road and then connected to Rennies River at Judge Place.

Conclusion

In general, nearly every small stream / brook we find is long gone. Some larger streams still exist in some fashion or another, however with many having their primary source disconnected via development, they are barely noteworthy. Many brooks still exist but have been completely converted into storm piping that discharges into one of the major rivers.

I think it is interesting that despite many brooks being lost to time, their location remains a park or green space. That may have been good stewardship by folks who have long since past, or maybe a fluke of property boundary disputes. At least these days removing a brook or stream is difficult, assuming a council doesn’t change a regulation.

We hope this shows the history of how building streets put many small brooks in pipes. A brook with an adjacent walkway is certainly better for people than a pipe in a road but inevitably, development changes how these brooks function. More people focused walking spaces are certainly a nice thing to try and maintain.

Thanks for this interesting post. There’s lots of interest in buried streams and daylighting these days, and of course we do now see them as amenities. I think it’s important to remember that in the early days, especially before WWII, small urban waterways were regarded as hazards. They were often polluted with sewage and industrial waste (in the days before proper sewerage and drainage), as well as garbage, etc. And hydrologically they provided (in some cases) a ready template for sewers and storm drainage when they were built–most sanitary engineers at the time recommended just that. I had a student do some work on the early sewerage and drainage of St. John’s if you’re ever interested.

LikeLike