As part of the Paris Agreement, Canada committed to net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Achieving that goal will require deep emission reductions across all sectors. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has identified the importance of urban systems in delivering these reductions via ‘land use planning to achieve compact urban form, co-location of jobs and housing, and supporting public transport and active mobility’. The City of St. John’s (CSJ) has an important role to play in a regional capacity, but we will focus on what changes St. John’s Council can make under their own power by facilitating higher urban density. Two immediate changes St. John’s can invoke are to remove parking minimums from its development regulations and add multi-unit residential buildings to the permitted uses of Residential Zone R1. In the following paragraphs, we will explore these potential changes and the impact they could have.

Transportation is a large component of Newfoundland and Labrador’s carbon footprint, accounting for 40% of total emissions. Personal light vehicle use accounts for 24% of NL carbon emissions. In order to reduce a large portion of our carbon emissions, we need to find ways to make urban transportation more efficient. Reducing dependence on individual vehicles and increasing ridership of public transit and use of active transit can deliver those reductions. Based on data from U.S. cities, it’s projected that a modest increase in public transit ridership of 9% could eliminate 166,000 cars worth of CO2 emissions annually. A more ambitious increase in ridership of 25% can eliminate 13,260,000 cars worth of emissions. While St. John’s wouldn’t see reductions of that magnitude, the data demonstrates how emissions reductions scale exponentially with uptake of public and active transit. Urban density is proven to incentivize pubic and active transit use, as well as providing additional benefits.

Residential energy use is also an important factor regarding carbon emissions. Space heating and cooling account for 63% of residential energy consumption. Apartment building and multi-unit dwellings that are typical in higher density development are more thermally efficient and can reduce energy use by 10-30%.

The CSJ’s development regulations specify a minimum number of parking spaces required for developments. Parking incentivizes car use, and increases the financial cost and physical footprint of developments. Removal of minimum parking requirements in US and Canadian jurisdictions has been proven to reduce the amount of parking built by developers. Removing parking minimums will lower the incentive to use personal vehicles, making public transit more appealing. It will also free up space in urban areas for alternatives uses, including amenities or housing to increase urban density. Removal of roadside parking requirements can also generate space for bicycle infrastructure.

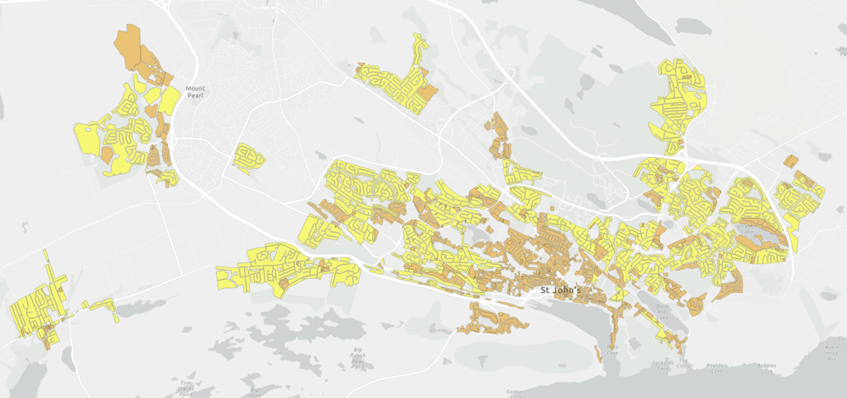

CSJ can further capitalize on the surplus space generated by reducing parking by making changes to their residential coning codes. 71% of the residential areas in CSJ are zoned R1. R1 zoning only allows construction of single detached homes, the most inefficient dwelling type spatially and thermally. The R1 zone should be updated to include duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, and townhouses as permitted uses. Six-unit apartments should also be added to the discretionary uses for R1 zoning. This would allow for substantial densification in the infill and redevelopment of already developed areas and enable higher density in future developments.

There would be opposition to these proposed changes. Car-centric development and culture are dominant in St. John’s. The convenience, freedom, and comfort of taking your personal vehicle everywhere is not something people want to be disincentivized — especially in rural areas . Increased density in residential areas would also impact property values of existing properties. As an alternative to urban density, we could consider electrification as an alternative.

Electric vehicles (EVs) do not produce operating emissions unless charged from a grid powered by fossil fuels. Also, the up-front carbon footprint of building an EV is higher than internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) due to the need for rare earth minerals in the production of their batteries. Despite those drawbacks, EVs have a lower lifecycle carbon footprint than ICEVs. Newfoundland’s power grid is over 91% fueled by renewable energy sources, so the carbon savings of EVs are substantial. Regarding home heating, new homes are all built with electric heating and there are incentives for converting homes and businesses from oil to electric heat. Electrification and Newfoundland’s primarily renewable grid can reduce the carbon footprint of home heating and transportation, delivering deep carbon reduction. All of this can be accomplished without the disruptive impact of densification, or the need for major behavioral changes in personal transportation.

Electrification seems attractive as an alternative policy to urban density but suffers from several shortcomings. First, there are other benefits that urban density delivers, but electrification does not. Increased density is part of the national strategy on increasing the housing supply. Higher use of active transportation also provides health benefits by reducing physical inactivity. Second, electrification does not address the other carbon emissions entailed in urban sprawl. Sparse development increases the need for supporting infrastructure (i.e. roads, sewers, power lines) which has its own carbon footprint. The concrete and asphalt required for road construction are especially carbon intensive components. Third, leaning heavily into electrification will require more generation capacity. Exchanging usage of ICEVs for EVs will increase demand on the power grid. Electrifying home heating, but favouring thermally inefficient single detached homes will increase power demand. Large capitol projects like power generation have massive carbon footprints. Renewable power can mitigate this carbon debt over its lifetime. However, if the necessary firm power capacity cannot be maintained with wind or solar power, thermal generation may be required.

Urban density can reduce power demand for home heating via increased thermal efficiency and facilitating more fuel/energy efficient transit via public and active transportation. Electrification is an important strategy in climate action, but it must be tempered by efforts to mitigate the demand for power consumption. Increased urban density can help deliver deep emissions cuts in the transportation sector through facilitation of energy efficient public transport and active transport. Density also provides demand side management options in the energy sector through curtailing home energy use and reducing the load growth of transportation electrification. CSJ can immediately begin facilitating increased density by removing parking minimums from the development regulations and adding multi-unit options to the permitted uses of residential zone R1. Additional benefits in housing supply and public health can also be found through densification. CSJ has the potential to be a leader on the Northeast Avalon to spearhead responsible development policies that prioritizes people and the environment over cars.